What Is Slippage and How Can It Be Managed?

Understand what is slippage with clear examples. Learn why it happens in crypto and discover practical strategies to minimize its impact on your trades.

Oct 20, 2025

generated

what is slippage, crypto trading, slippage tolerance, market liquidity, trading costs

In financial markets, you may have encountered a situation where you click 'buy' on an asset at a specific price, only to find the final executed price is slightly different. This small, often frustrating, price discrepancy is known as slippage.

It represents the difference between the price you expect to pay for an asset and the price you actually pay when the transaction is completed.

The Hidden Cost of Execution

Whether you are trading digital assets, equities, or foreign exchange, slippage is a fundamental reality of market execution. It occurs in the brief delay—often just milliseconds—between the moment an order is placed and the instant it is filled by an exchange or liquidity provider.

This price difference can occasionally work in your favor (positive slippage), but more commonly, allocators are concerned with negative slippage—where an asset is purchased for slightly more than expected or sold for slightly less.

For a small retail trade, the impact may seem negligible. However, for institutional-sized orders, these small discrepancies can compound into significant costs. Analyses of U.S. equity markets, for instance, have found that slippage can cost traders an average of 10 to 15 basis points per trade. Across a large portfolio, this represents a material drag on performance.

Key Takeaway: Slippage is not an exchange fee. It is a natural market phenomenon driven by price volatility, order size, and available liquidity at the time of execution.

To better understand how slippage can manifest, it is useful to compare its different outcomes.

Slippage Scenarios at a Glance

This table outlines the three potential outcomes when a trade order is executed in the market.

Type of Slippage | Description | Impact on Allocator |

|---|---|---|

Negative Slippage | The execution price is worse than the expected price (e.g., buying higher or selling lower). | Unfavorable. This is the most common form and results in a less profitable or more costly trade. |

Positive Slippage | The execution price is better than the expected price (e.g., buying lower or selling higher). | Favorable. The executed price is better than anticipated, though this is less common, particularly in volatile markets. |

Zero Slippage | The execution price is identical to the expected price. | Neutral. This is the ideal outcome, often observed in highly liquid markets for smaller order sizes. |

Ultimately, understanding the mechanics of slippage is the first step toward minimizing its impact. While it is an inherent cost of transacting in dynamic markets, it can be effectively managed with the right strategy and execution tools.

The Market Dynamics Behind Slippage: Volatility and Liquidity

Slippage is not a random occurrence; it is a direct consequence of fundamental market mechanics. Two primary forces are almost always responsible for the gap between an expected price and an executed price: market volatility and liquidity. For any serious allocator, from retail investors to institutional desks, understanding the interplay between these two factors is essential.

Volatility can be thought of as the rate of price change in a market. In calm conditions, prices tend to move predictably. However, when significant news or economic data is released, market volatility can increase sharply, causing prices to fluctuate rapidly.

A trade order, which requires a fraction of a second to process, is submitted into this environment. That small delay is sufficient for the price to move. If the price moves against the order during this window, negative slippage occurs. The greater the volatility, the larger the potential price swing before an order is filled.

This infographic illustrates the two core drivers—volatility and liquidity—that directly impact trade execution quality.

As shown, high-volatility environments (the lightning bolt) and shallow, illiquid markets (the single droplet) create the ideal conditions for significant slippage.

The Role of Liquidity in Order Execution

If volatility is the market's pulse, then liquidity is its depth.

Consider a highly active market with numerous buyers and sellers at various price levels—this is a high-liquidity scenario. A large buy order can be absorbed with minimal price impact because there are sufficient sellers at or near the current market price.

Conversely, an illiquid market has few active participants. If the same large buy order is placed here, there are not enough sellers to fill it at the best available price. The exchange's matching engine must move up the order book, filling the order at progressively worse prices. This is a clear demonstration of how low liquidity causes slippage.

This is particularly critical for HNWIs and institutional investors placing large orders, as their trades are often large enough to consume all available orders at the best price. A thorough understanding of liquidity in cryptocurrency is therefore a prerequisite for effective trading strategies.

In summary, slippage is primarily caused by two interconnected factors:

High Volatility: The price changes too quickly for the order to be filled at the expected level.

Low Liquidity: There are not enough resting orders on the book to absorb a trade without moving the price.

When both conditions are present—a volatile, thinly-traded market—the risk of significant slippage increases substantially. For any serious allocator, analyzing an asset's trading volume and market depth is as important as evaluating its price chart.

How Slippage Functions in CEX vs. DEX Environments

Slippage does not behave uniformly across all trading venues. Its mechanics differ significantly between centralized exchanges (CEXs) and decentralized exchanges (DEXs). For allocators evaluating both CeFi and DeFi strategies, understanding these structural differences is crucial for effective risk management.

The Order Book Model on Centralized Exchanges

On a CEX, trading activity is centered around the order book—a real-time ledger of all buy and sell orders for a given asset. When a market order is placed, the exchange matches it against the best available prices on the book.

If an order is small relative to the total volume, slippage will likely be minimal. However, a large institutional order can consume all liquidity at the best price and begin filling at the next-best price levels further down the book. This price impact is a direct function of trade size relative to the available supply of counter-orders.

For this reason, a detailed analysis of the depth of the market is a standard component of institutional execution strategy.

The Algorithmic Model of Decentralized Exchanges

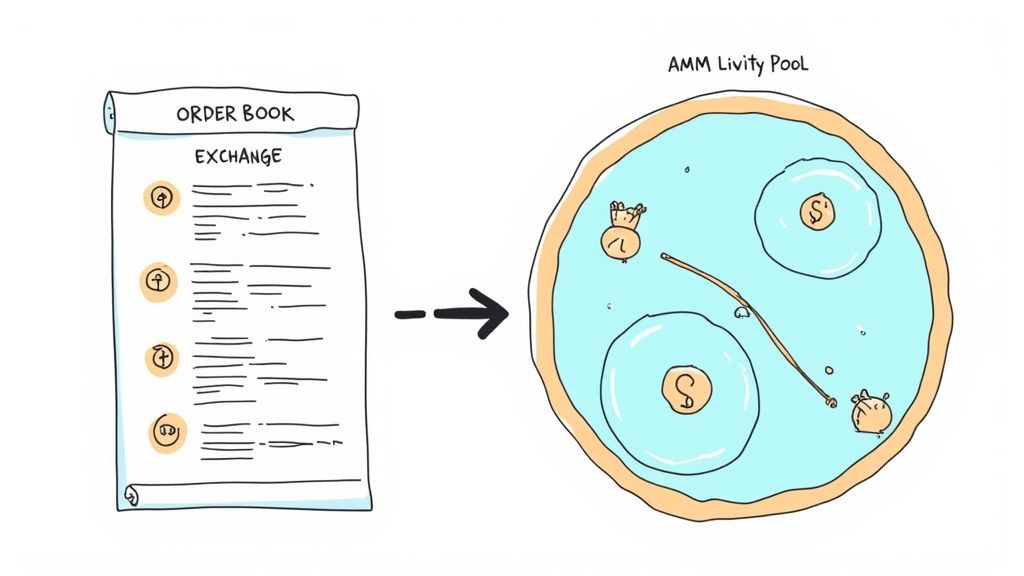

DEXs operate under a different paradigm. Most utilize Automated Market Makers (AMMs) and liquidity pools instead of traditional order books.

In an AMM model, prices are determined by a mathematical formula that maintains a constant balance between two assets in a pool. Slippage is not an incidental outcome; it is a predictable, built-in feature of the design. Every trade adds one token to the pool and removes another, which alters the asset ratio and, consequently, the price.

The larger a trade is relative to the total size of the liquidity pool, the greater the price impact and the more slippage will be incurred.

The pool's size, or Total Value Locked (TVL), is therefore the single most important factor for DEX traders. Slippage on a DEX is less about market speed and more about the mathematical relationship between the trade size and the pool's depth. A multi-million dollar swap in a small, illiquid pool will almost certainly incur significant slippage because it dramatically rebalances the asset ratio.

This fundamental difference is why risk assessment for CeFi and DeFi requires two distinct analytical frameworks.

Comparing Slippage: CEX vs. DEX

To summarize, this table breaks down how the two environments compare in the context of slippage.

Factor | Centralized Exchanges (CEX) | Decentralized Exchanges (DEX) |

|---|---|---|

Pricing Mechanism | Traditional order book with bid/ask spreads. | Algorithmic, based on asset ratios in a liquidity pool. |

Primary Cause | Trade size exceeding available liquidity at the best price levels. | Trade size representing a large percentage of the total liquidity pool. |

Predictability | Less predictable; depends on real-time market activity and hidden orders. | Highly predictable; can be calculated based on pool size and trade amount. |

Key Metric | Order book depth and trading volume. | Total Value Locked (TVL) in the liquidity pool. |

Mitigation | Break large orders into smaller ones (algorithmic execution); use limit orders. | Select high-liquidity pools; utilize slippage tolerance settings. |

Ultimately, whether trading on a CEX or a DEX, the core challenge remains the same: accessing sufficient liquidity. However, the structure of that liquidity dictates the appropriate strategies for managing slippage risk.

Practical Strategies to Reduce Slippage

Understanding the causes of slippage is one part of the equation. The other is implementing strategies to actively manage it. A robust toolkit of techniques is available to help protect capital and improve execution quality across both centralized and decentralized venues.

These are not just tactics for large institutional desks; they are fundamental strategies that give all allocators, from individual traders to family offices, greater control over their execution outcomes.

Use Limit Orders Instead of Market Orders

The most direct method to eliminate negative slippage is to avoid using market orders. A market order instructs an exchange to execute a trade immediately at the best available price. It prioritizes speed over price, which creates exposure to slippage.

A limit order, in contrast, provides price control. The user sets the specific price at which they are willing to transact.

Buy Limit Order: This sets the maximum price you are willing to pay. The order will only be filled at your specified price or lower.

Sell Limit Order: This sets the minimum price you are willing to accept. The order will only be executed at your specified price or higher.

The primary trade-off is that a limit order is not guaranteed to fill if the market never reaches the specified price. However, the benefit is complete protection against negative slippage.

Set Slippage Tolerance on DEXs

Decentralized exchanges offer a specific tool called slippage tolerance. This setting allows a user to define the maximum percentage of price movement they are willing to accept for a transaction to proceed.

By setting a tight slippage tolerance—for example, 0.5% or 1%—you instruct the DEX to automatically cancel the transaction if the final execution price deviates beyond this limit. This is a critical risk management feature, especially when trading volatile or thinly traded assets.

Execute Large Orders in Smaller Increments

Placing a single, large order on the market is a guaranteed way to create significant price impact and incur slippage. A more prudent approach is to break the large position into several smaller trades and execute them over a period of time.

This technique, often automated with execution algorithms (e.g., TWAP, VWAP), dramatically reduces market impact. It allows the market to absorb each smaller part of the order without causing adverse price movements. Mastering these mechanics is central to effective crypto market making and institutional-grade execution.

Trade During Peak Liquidity Hours

Financial markets have distinct periods of high and low activity. To minimize slippage, it is best to trade when liquidity is at its peak. For the 24/7 digital asset market, this often occurs during the overlap of major regional trading sessions (e.g., US and Europe).

Greater liquidity means a deeper pool of buyers and sellers. This depth helps absorb orders more efficiently, resulting in tighter spreads and a lower probability of significant slippage. This principle applies across asset classes; in forex, for example, slippage of 0.5 to 2 pips during active hours can increase substantially during illiquid overnight sessions or news events.

Quantifying the Impact: How to Calculate Slippage

To effectively manage slippage, one must first measure it. Moving beyond a conceptual understanding to quantifying its financial cost is a critical step for any serious allocator. This transforms slippage from an abstract risk into a concrete metric that can be tracked and optimized.

The calculation is straightforward, measuring the financial gap between the expected and actual execution prices.

The Basic Slippage Formula

At its core, the formula is a simple calculation of the price difference multiplied by the quantity traded.

Slippage Cost = (Expected Price – Execution Price) * Order Size

Let's illustrate with a practical example.

An investor intends to purchase 2 BTC. The quoted price on the screen is $60,000. Due to the order size and market conditions, the trade is filled at an average price of $60,050.

Using the formula:

Expected Price: $60,000

Execution Price: $60,050

Order Size: 2 BTC

Slippage Cost = ($60,000 - $60,050) * 2 = -$50 * 2 = -$100

In this transaction, the investor paid an additional $100 due to negative slippage. This is a direct cost that reduces the potential return on the investment.

This type of measurement is a key component of the Transaction Cost Analysis (TCA) reports used by institutional investors and family offices to evaluate the performance of their strategies, brokers, and trading venues.

Frequently Asked Questions About Slippage

To conclude, let's address some of the most common questions allocators have regarding slippage.

Is Slippage Always Negative for a Trader?

Not necessarily, but positive outcomes are not a reliable basis for a strategy. While most concern is focused on negative slippage (receiving a worse price), its counterpart, positive slippage, can also occur. This is when the market moves in your favor during order execution.

For example, a buy order for BTC placed at $60,000 might fill at an average price of $59,980. This represents positive slippage. However, a sound investment strategy should focus on mitigating downside risk (negative slippage) rather than relying on chance.

What Is a Standard Slippage Tolerance on a DEX?

For most trades involving major asset pairs on large decentralized exchanges, a slippage tolerance between 0.5% and 1% is a common starting point. When trading a highly volatile or less liquid altcoin, it may be necessary to increase this to 2-3% to ensure the transaction can be processed.

Key Insight: Setting a tolerance too low (e.g., 0.1%) on a volatile pair can lead to frequent failed transactions. The goal is to find a balance between protecting your entry price and ensuring successful trade execution in a dynamic market.

How Does Slippage Differ from Transaction Fees?

This is a critical distinction. Slippage and transaction fees are two separate and distinct trading costs.

Transaction Fees: These are explicit, predictable costs charged for using a platform or blockchain network (e.g., exchange trading fees or Ethereum gas fees).

Slippage: This is an implicit, variable cost that arises from market movements between the time an order is placed and when it is executed.

A successful trading strategy requires effective management of both explicit fees and implicit costs like slippage.

Gain a clearer perspective on the digital asset investment landscape with Fensory. Our platform is designed to provide sophisticated allocators with the data-driven insights and discovery tools needed to perform institutional-grade due diligence on BTC and stablecoin products. Explore Fensory today.